Elmore Leonard always seemed like one of those authors I should get around to reading. He was a popular writer, and in my mind I associated him with a Dennis Lehane or a James Ellroy. Not that I would know—I’ve never read them either. Like most voracious readers, my bookshelf is stocked with books I will never read by authors I’ve been told I will like.

So, when Leonard passed away last month at the age of 87, I decided to pay tribute to “the Dickens of Detroit” by sampling his work. Not knowing where to start, I picked up Get Shorty, Leonard’s 1990 book about a shylock who becomes a movie producer. Appropriately enough, it was later made into a movie starring John Travolta (with Danny DeVito as the titular “Shorty”).

I was slightly concerned to be reading the book, having already seen the film (albeit 15 years ago). While movie adaptations are seldom as good as their source materials, it’s hard to go back and read a book after the movie has given you a vision of the characters.

But in Leonard’s case, it’s nearly impossible to read a book of his that hasn’t been adapted. His works have spawned a whopping 23 films and 3 television series (the most recent of which is the FX series “Justified”).

Some authors’ works get made into movies because they have a large readership. Stephen King writes a book, millions of people read it, and the movie sells itself to a pre-existing audience. Some authors’ works get made into movies because they have a name. Tom Clancy and his ghost writers churn out books, and his name gets attached to the film so people will see it. Never mind that the book and movie have nothing in common. His 1991 paperweight The Sum of All Fears featured Arab villains. The movie adaptation, released one year after the September 11th hijackings, opted for political correctness by turning the villains into…neo-Nazis. Apparently, someone thought they were making a comeback. Still other writers get the movie treatment solely based on concept. The plot of Philip K. Dick’s story “The Minority Report” bears little resemblance to that of the movie starring Tom Cruise. But, it didn’t matter because Dick’s concept alone could have spawned dozens of intriguing plots.

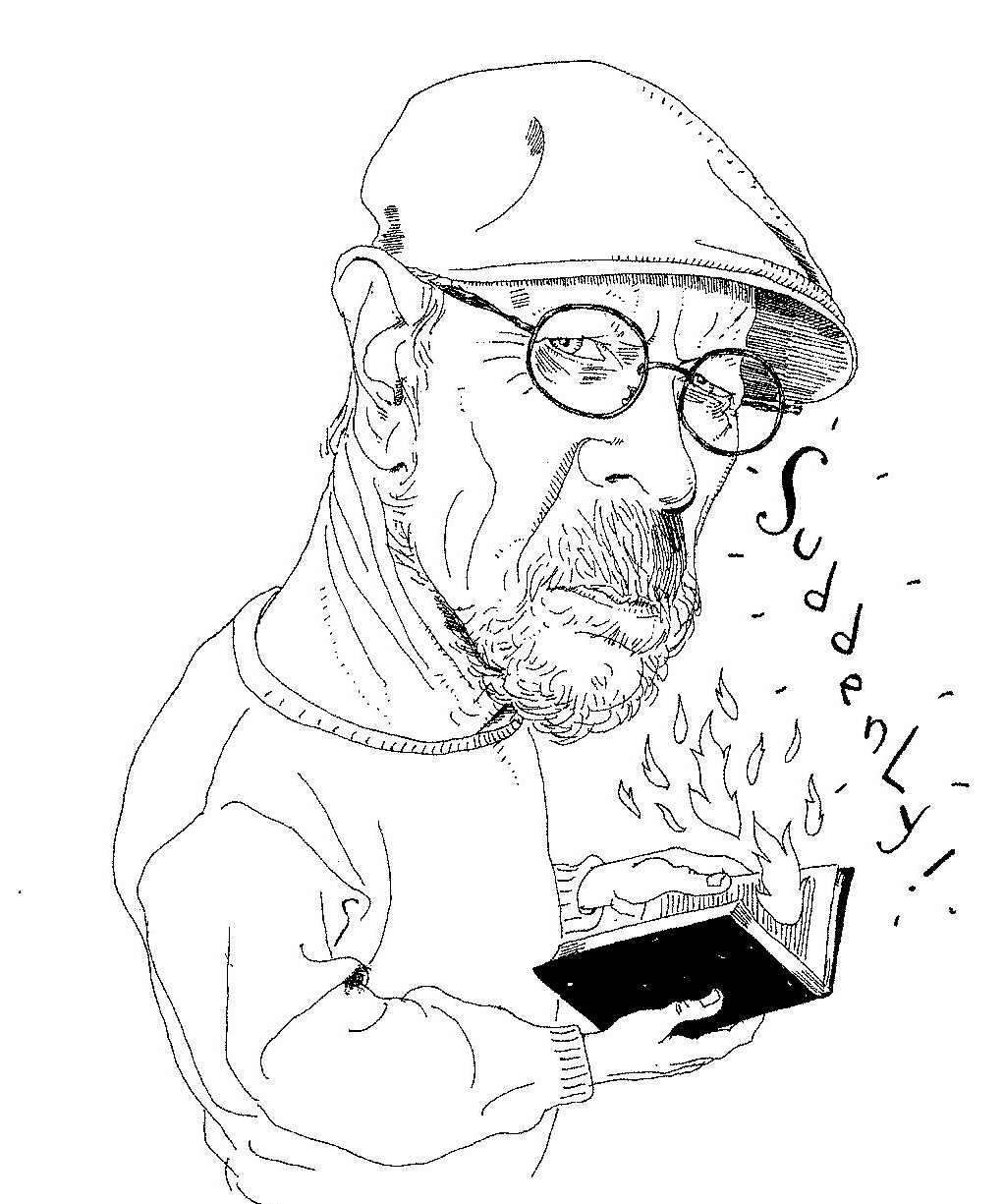

Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.Elmore Leonard

Elmore Leonard’s books get turned into movies because they read like scripts to begin with. The author admitted as much in an interview with novelist Martin Amis: “I don’t think there’s any question that it’s difficult for movies to internalize. The reason I’ve been able to sell all my books is because they look like they’re easy to shoot.” This is not by coincidence. The golden rule of his famous 10 Rules of Writing is: “If it sounds like writing…rewrite it”. It’s part of a larger rule that states: “Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.” As Leonard put it:Think of what you skip reading a novel: thick paragraphs of prose you can see have too many words in them. What the writer is doing, he’s writing, perpetrating hooptedoodle, perhaps taking another shot at the weather, or has gone into the character’s head, and the reader either knows what the guy’s thinking or doesn’t care. I’ll bet you don’t skip dialogue … If I write in scenes and always from the point of view of a particular character — the one whose view best brings the scene to life — I’m able to concentrate on the voices of the characters telling you who they are and how they feel about what they see and what’s going on, and I’m nowhere in sight.

Leonard skips describing sunsets and giving detailed explanations of what is happening. It’s all dialogue, and if it’s not, he uses inner monologue to explain what’s going on. So it comes out with the same vivacity as dialogue. Listen to how he gets out of the way and harnesses the inner monologue of one of his characters (not even the protagonist) to describe a scene:

Catlett liked to watch people going by, all the different shapes and sizes in all different kinds of clothes, wondering, when they got up in the morning if they gave two seconds to what they were going to wear, or they just got dressed, took it off a chair or reached in the closet and put it on. He could pick out the ones who had given it some thought. They weren’t necessarily the ones all dressed up, either.

The young dude in the jeans and the wool shirt hanging out, he’d given that outfit some thought. A friendly young dude, said hi to the ladies behind the airline counter and they said hi back like they knew him.

Leonard’s novel (I can’t speak to any of his work beyond the one book of his I’ve read) is a master class in characterization. His characters think and talk like people really think and talk. Ever read a book that has 10 different flowery ways to describe a sunset but sounds like it’s been written by someone who lives in his mother’s basement and has never witnessed any actual human interaction? Leonard is the antidote. He writes like’s he’s transcribing a tape recorder he stuck inside someone’s brain.

He writes like’s he’s transcribing a tape recorder he stuck inside someone’s brain.

It’s odd that I’ve come to a sudden appreciation of Elmore Leonard as I sit down to write my own novel. Whereas Leonard the writer makes sure to get out of the way of his characters, my prose is startlingly self-conscious. (And, yes, I did just break one of his ten rules by using an adverb.) My writing sounds like someone has written it. And I think I’m okay with that. Reading a little bit of “hooptedoodle”, provided it’s good hooptedoodle, isn’t going to kill the literati who still buy novels in bookstores instead of airports. Yet aspiring authors like me can learn a lot from Leonard—for instance, how to avoid two pages of exposition when a line of dialogue can get you there just as well. Now I just need to figure out where to get that tape recorder.